The shutdowns implemented in response to the Wuhan virus pandemic have made the economy spiral into a recession. Additionally, this crisis will add significantly to the national debt.

Chris Edwards, the Director of Tax Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, wrote a piece about what this could potentially entail.

Treasury Secretary Mnuchin recently said that “interest rates are incredibly low, so there’s very little cost of borrowing this money.”

Edwards countered Mnuchin’s assertion by declaring that it “is not correct.”

He expanded:

Mnuchin seems to have forgotten about loan principal. Every dollar borrowed causes damage down the road from the resulting higher taxes extracted from the private sector. Furthermore, interest rates may spike, which will increase federal borrowing costs as accumulated debt is rolled over.

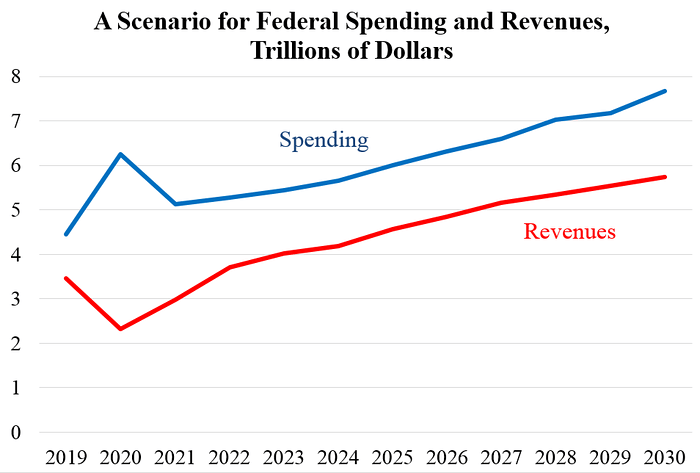

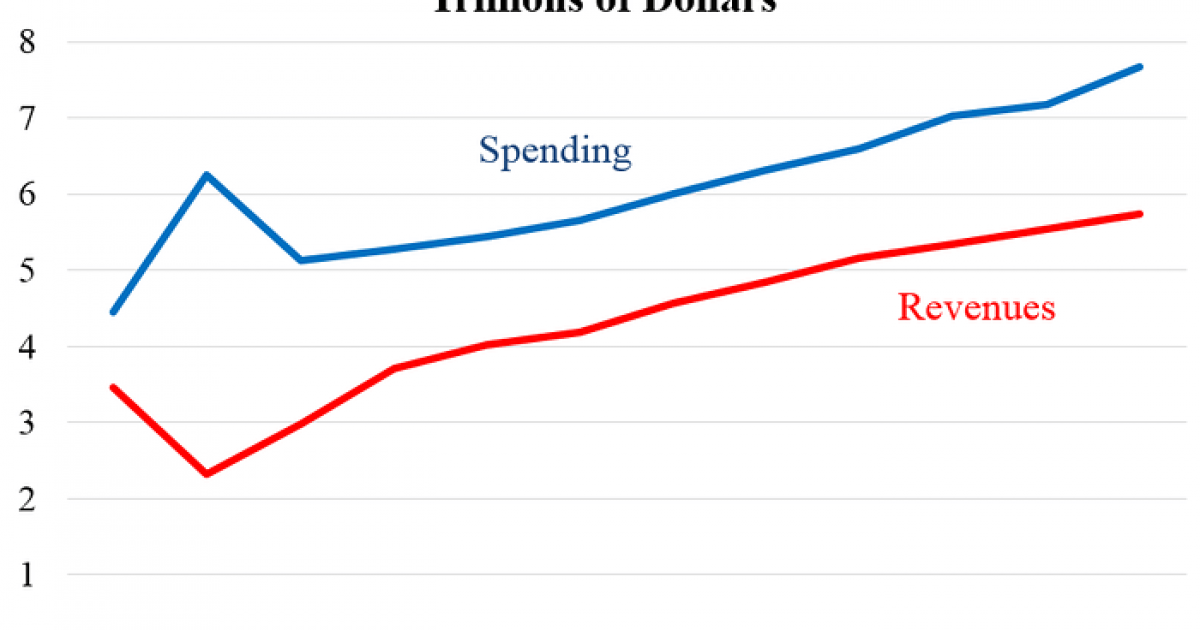

Edwards is of the belief that recent spending binges could add $6 trillion to the national debt “based on the rough spending and revenue scenario shown in the chart below.”

He started off by showing how recent spending packages would impact the national debt:

The spending and tax cuts in the CARES Act will increase debt by $1.76 trillion. The prior relief package called Families First will increase debt by $192 billion. Add to that perhaps $450 billion for a further relief bill that Congress may soon pass. In total, spending increases and tax cuts in coronavirus legislation may increase debt about $2.4 trillion.

Edward asserts that debt will increase even further because the recession is causing federal revenues to plummet.

The Cato scholar drew from the experience of the previous recession to illustrate his point:

During the last recession, revenues fell 18 percent between 2007 and 2009 and took five years to recover to the prior level. For the current scenario, I assumed revenues will fall 18 percent this year due to the recession and then start to recover and regain the CBO baseline level by 2025. Under that scenario, the revenue losses will be $2.2 trillion.

Edwards called attention to the fact that “With higher spending and lower revenues, federal borrowing costs will be roughly $1.2 trillion higher over the coming decade.”

According to his chart, the deficit is expected to skyrocket to $3.9 trillion in 2020, “then narrowing to about $1.5 trillion for a few years before widening again.”

From 2019 and 2030, the federal government is projected to add $20 trillion in new debt if its spending habits do not change.

Edwards offers a bleak picture of what the U.S.’s fiscal woes will look like in the next decade:

Under the CBO baseline, federal debt held by the public had been expected to rise from $16.8 trillion in 2019 to $31.3 trillion by 2030, or 79 percent of GDP to 98 percent. Under my scenario, debt will rise to $37.2 trillion by 2030 or 116 percent of GDP. The crisis may impose almost $6 trillion of costs on future taxpayers.

The Cato scholar put things into historical perspective:

The previous high federal debt‐to‐GDP ratio was 106 percent in 1946. That pile of debt was cut to 56 percent by 1955. Was that fall due to Congress being prudent and running surpluses? Nope. Instead, most of the drop in debt‐to‐GDP from 1946 to 1955 was due to substantial inflation that reduced the debt’s real value.

Edwards posed the following question: “Will the government try to use the same technique to cut its record debt this time?”

History has shown that financially reckless governments end up having debt crises.

One way they try to alleviate these disastrous scenarios is by inflating the currency in order to reduce the debt’s overall value.

However, inflation is a dangerous proposition since it completely eradicates everyday people’s savings once a national currency is destroyed.

It would probably be best that the U.S. avoid this situation altogether by getting its fiscal house in order and pursuing a less expansionary monetary policy.